How do AAA games make their worlds feel alive and interesting, even if all the player is doing is walking down the street?

They consider their worlds as living entities, not just static backdrops.

One way they do this is by using movement within their game world to tell a story.

Let’s look at a simple, specific example…

Here is a game scene from our RPG that we’ve been developing. The player is progressing along their path, heading towards the next steps of the quest we’ve created for them.

In our game, like most RPGs, we’re using combat as a primary system of challenge and interest… but of course we don’t want to have one, long, continuous combat sequence.

In this instance, what are our options for communicating story to the player?

Well, we can have the player bump into an NPC and deliver some dialogue. That is usually the most to-the-point way of getting story across.

For example:

Crazy Bill: Quick, the town is under attack, the villagers need help.

Player: Rightio Bill, I’ll get right on that.

Or we can pop up a dialogue box on the screen saying something to the effect of:

“The town is under attack, go see if the villagers need help”.

We can trigger a non-interactive cut scene, we can have a narrator do a voice over, we can have the player speak to themselves such as “oh golly, look at that, the town is on fire”.

Or, (and this is where we arrive at the point of this article) we can apply the…

–> “show them, don’t tell them” rule <–

…that is a common tool in a movie scriptwriter’s arsenal.

How would we do that in this example?

Well, as the player reaches a certain point, we could have villagers running away from the village flailing their arms and yelling, “help, help”. Even better, we can have some smoke billowing from the direction of the village. Perhaps even trigger a little explosion to show that something flammable was just hit. Or we could simply have a view where the player can see the village off in the distance, on fire.

Why is this “show them, don’t tell” approach good for your game?

Well, it gives the player the opportunity to “figure it out”. To put 2 and 2 together. To read between the lines.

Which hopefully will make them feel clever and in control as they are playing your game. And as your player progresses through your game and learns the language of the clues you are giving them, you can be increasingly subtle and have them feel increasingly clever.

How can we do this in Unity?

There are a few ways to skin this cat.

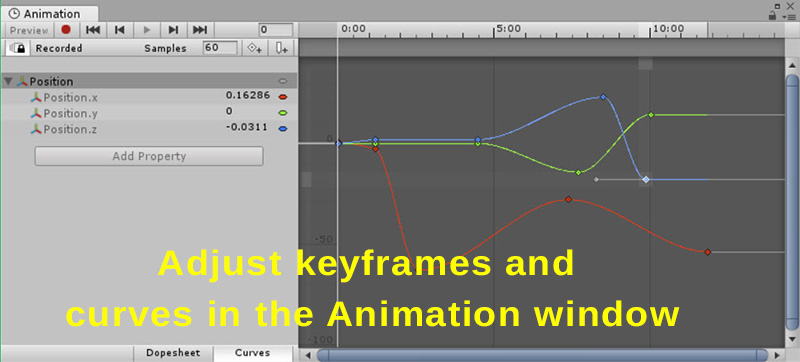

One simple approach is to create a trigger volume that is linked to an animation. The animation that gets triggered could be as basic as a character (an NPC) running from A to B across the path of the player. This can be done with Unity’s animation system.

And then, attach a simple fire particle system to them, or a smoke particle system, and it could create the impression that they are on fire.

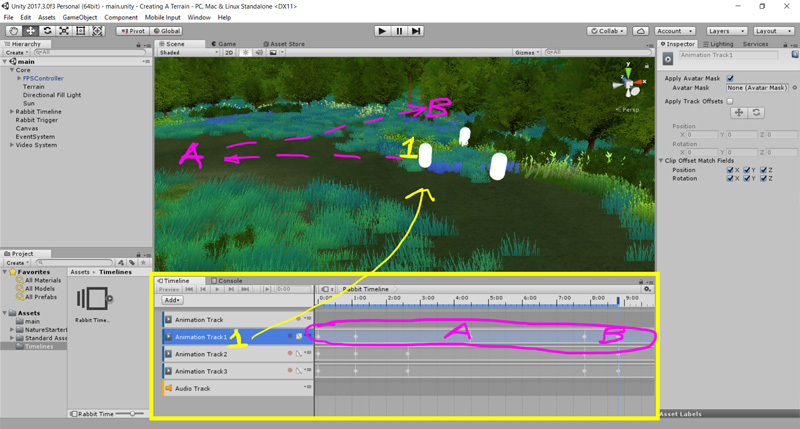

Even cooler is that you can create more complex sequences (including multiple animations or events) using Unity’s Timeline tool (which is available in Unity 2017 onwards). Timeline gives you the ability to orchestrate a more detailed game moment by controlling many related events from the one timeline.

The control you have over giving depth to your story is huge.

For example, you could use Timeline to have one first villager run to a certain point, stop, yell at another villager, at which point that second villager runs off as well, shortly followed by a flaming tree falling over and a dog yelping as it takes flight to get away from the fire.

In the diagram above we have 3 animation tracks and 1 audio track, all coordinated to start based upon the player reaching a trigger volume on our map.

You can also use Timeline to build gameplay moments

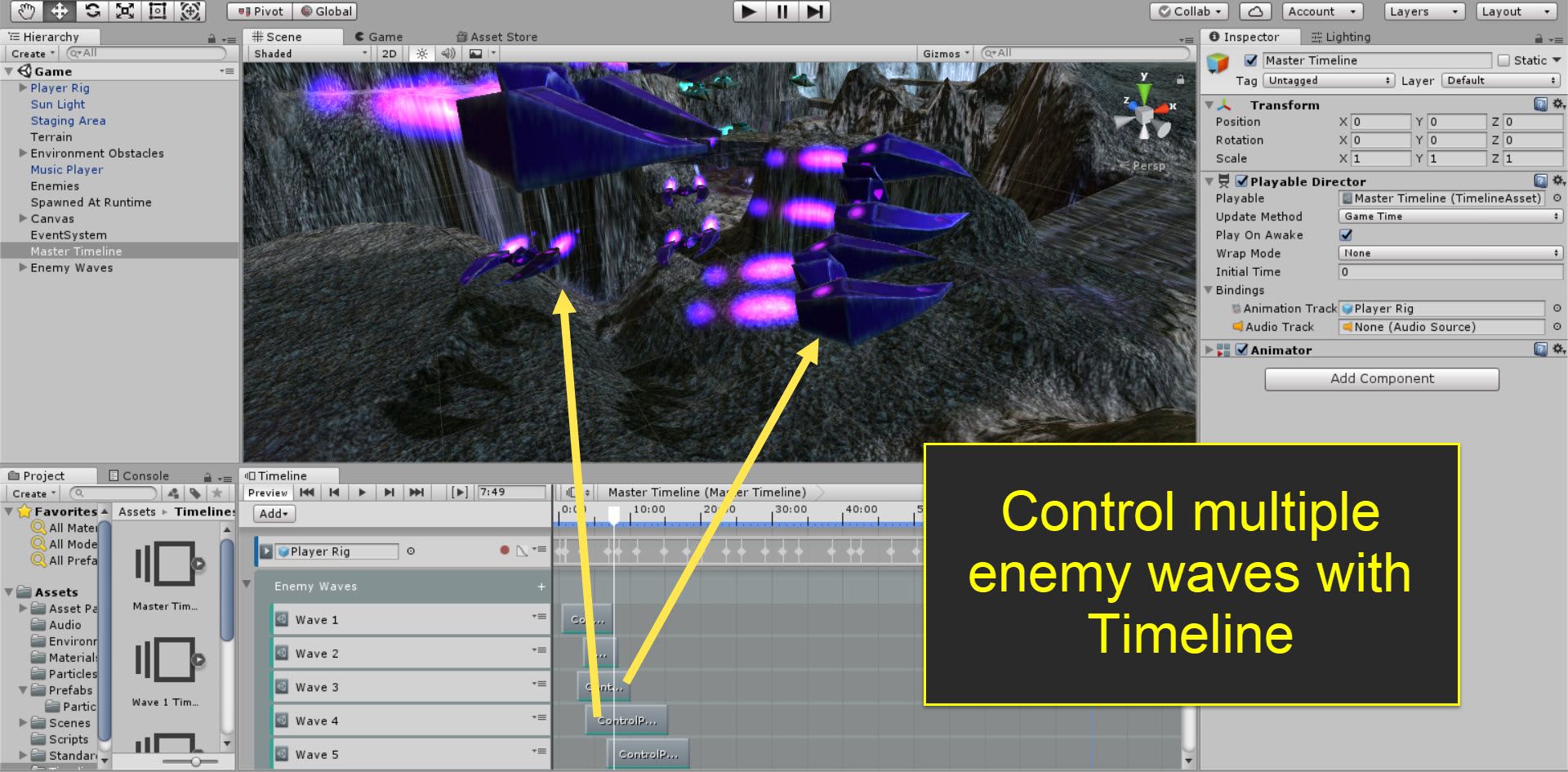

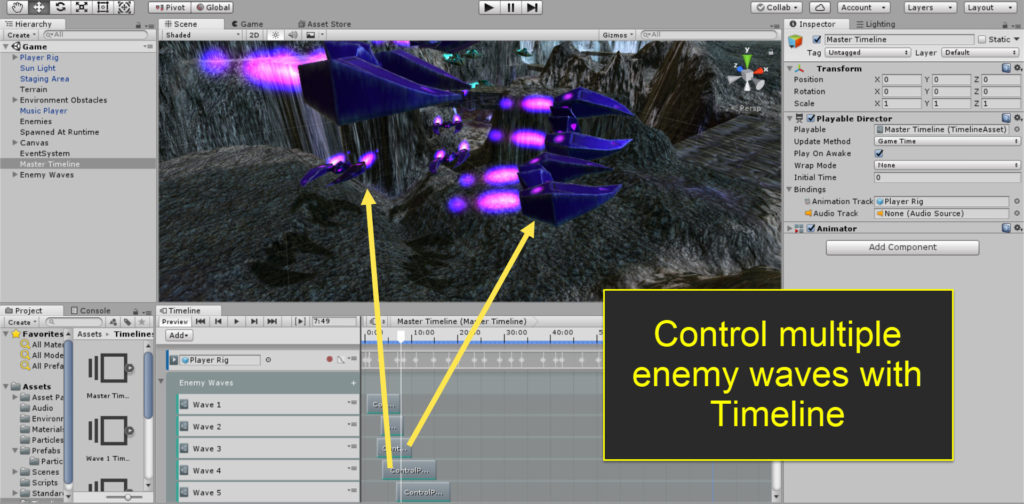

Timeline can be used for more than background flavour. You can use it to organise enemy patterns and behaviours, such as the approach we’ve taking in our Rail Shooter game that we teach in our newest Unity course (The Complete Unity Developer 2.0).

The idea is that each Timeline sequence can be created with great precision and detail to make the whole game feel very cinematic. And because the enemies can take damage and be destroyed, we have combined the best of “cinematic world building” with “gameplay challenge and skill”.

And as we blur the line between “interactive” sequences and “non-interactive” sequences, the player will come to feel that everything in the world could be part of the gameplay and therefore important to pay attention to.

Learning more…

If you’re interested in learning more about creating cinematic feeling games or Unity’s Timeline tool, then click this link to check out our Complete Unity Developer 2.0 course (complete with a coupon code with a big discount to the course for our blog readers).

Until then, happy gamedevving!